Scientific journals often let you suggest potential peer reviewers for your manuscript. This is usually done in the cover letter, though some journals may also have a place to input them online.

Suggesting reviewers has many benefits, and some journals even require it. On reasonable grounds, you can also request to exclude individual reviewers or labs from the review process.

Many authors make the mistake of recommending colleagues or scientists with inadequate knowledge of the subject matter. By making good, diverse recommendations, you can help ensure your paper gets an effective and rigorous review, make the journal editor’s job easier, and speed up the peer review process. Reviewers can range from Ph.D. candidates to lab-leading professors, giving you a huge pool to choose from.

Follow these tips to recommend a suitable list of reviewers for your scientific manuscript.

What you’ll learn in this post

• How and where to suggest peer reviewers when you submit your manuscript for publication.

• The right type and number of reviewers to suggest.

• What to avoid in your recommendations so that the journal editor will appreciate and use your suggestions.

• How Edanz can help you choose reviewers and speed you along the path to publication.

Recommend 4 or 5 reviewers (not 1, not 10)

When a journal requires reviewers, it’s usually a minimum of two (as with this major publisher), but proposing 4 or 5 reviewers is best. This will let you provide a more diverse and useful selection for the editor to choose from.

Reviewers are more likely to respond positively to a review request if they’ve been suggested by the authors rather than the editors. However, not all potential reviewers will reply and editors won’t always go with your suggestions

Still, suggesting 4-5 potential reviewers will give the editor a small but diverse pool to choose from and speed things up. This can supplement any reviewers the editors may already have in mind from their own networks.

Proposing more than 6 or 7 could actually make the editor’s job more difficult. They may just choose to go with reviewers from their own network, rather than trying to choose from your long list.

Choose at least one reviewer with very specific knowledge of your topic

Naturally, you should suggest reviewers with strong practical knowledge of your line of research. This can be challenging in very specific, niche areas, so your suggestion of one or two specialists will greatly help the editor. Your own professional network is the first place to look. Not coauthors or colleagues, but other professionals you may have met or be aware of, or second- or third-degree connections (e.g., someone that someone else in your lab knows). Beyond that, do a search similar to what you do with a literature review.

Use your own references

Your manuscript’s own references should offer some excellent leads for potential reviewers. After all, these are the works you cite in your background, literature review, and results. If you’re citing a paper, it’s definitely related to your topic.

Search for other publications

Target the authors of other existing publications. After going through your references, go through your saved articles (on your desktop, in your reference management software, etc.). More leads are there. After that, start searching.

Use databases such as IEEE Xplore, Science Direct, and PubMed. Start by searching keywords from your manuscript’s title, or use the title itself, and check for closely matched articles.

For example, the authors of “Formation mechanism of streamer discharges in liquids: a review” could have used PubMed Central to find the relevant references. This article is on plasmas in general, but specifically, it’s on the topic shown in the title. Searching with the title gives the following results. Many of these results aren’t relevant, and some are outdated. Still, with such a specific title, the first few pages of search returns are almost guaranteed to yield many candidate reviewers.

You can also use databases such as the Journal/Author Name Estimator (JANE), which finds related journals, authors, and articles with the search query. You can paste your abstract into the search box and click “find authors.” The engine will then generate a list of authors who have published on topics similar to your abstract. You can then go down the list of related authors and find their contact information.

Similar tools, like PubReMiner, provide an overview of the research areas and journals of the publications in which your query was published. You can also find the top-ranked authors associated with your query, which you can then add as potential reviewers.

Publons is another source for searching for publications, citation metrics, and their peer review experience. This tool lets you search for qualified reviewers through their verified platform.

You should already have a target journal, so browse articles from that journal’s publications. Again, use your keywords or the manuscript’s title to do an internal search.

And research the researchers. For example, when suggesting a reviewer with specific knowledge in your area of study, be sure they’ve published in that area. Check to see if they have at least a couple of publications in your area. This will ensure you get valuable review comments from them, and it will reassure the editor that they’re getting credible scientific input from the reviewer.

Choose one or two reviewers who would understand your topic generally

Researchers who may not be specialists in your very specific area, but are in similar or intersecting areas, can offer a broader perspective. This is valuable for your peer review because it lets you see how your work fits into your larger area of science, and greater society.

Again, look at existing publications using search engines like those mentioned above. Check what’s already been published, and which articles are related to your general topic. Or which authors have published in your general area.

For example, if you specialize in self-efficacy among remote workers in various populations and professions, you can search for other organizational psychologists investigating self-efficacy. Or search for those investigating other psychological aspects of remote work.

Use your manuscript’s keywords as search terms. Also, use technical terms common in your field. The authors of the above physics example could use: “streamers”, “discharges”, “plasma”, and “discharges in liquids”.

Review articles (such as systematic reviews and narrative reviews) and meta-analyses on your topic can also be a goldmine of potential reviewers (not to mention, a goldmine of references for your research). Review paper authors have a good understanding of the big picture in the field and the latest developments in it. They will have a clear vision of where your paper fits within the field.

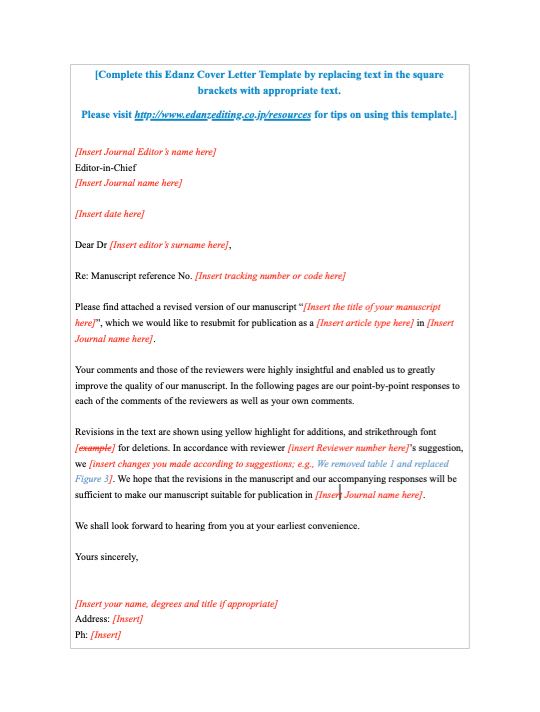

Peer review response letter template

Struggling to write that letter to the editor and peer reviewers? Try this free template! Simply replace the placeholder text with your own information, edit, and send with your detailed responses!

★ Pro Tip: Remember to double-check the spelling of the journal editor’s name!

Suggest geographically diverse and gender-diverse reviewers

You want readers around the world, and so do English-language scientific journals. Moreover, diversity and inclusion are now vital topics in the peer review process. Suggest peer reviewers that represent a wide geographic scope.

If you only suggest reviewers from your own country can lead to biases. For example, this study found that U.S. reviewers were more likely to give positive feedback to papers by U.S. scientists. That’s an extreme case, but certain biases are unconscious. Another study found that both editors and peer reviewers favored papers by authors of the same country (and gender).

The dominance of Western voices in peer review is an ongoing issue that journal editors are increasingly aware that they need to correct. However, regional preference between corresponding authors and the reviewers they suggest isn’t limited to the West. All cases of regional preference breed potential bias and hinder peer review’s objective of objective and impartial critique that produces valuable science.

Gender diversity is also an increasingly vital topic in academic publication (see this paper [PDF] for a deeper discussion on the topic). If possible, make sure your suggestions include both female and male scientists. Again, you’ll make your target journal editor’s life easier, and you’ll show them that you share their goals of global and gender diversity in peer review.

Choose reviewers you don’t personally know

It seems obvious that you shouldn’t choose researchers you personally know, yet authors continue to do this. It’s a waste of both the authors’ and the editors’ time, as the potential both for bias and for conflicts of interest is overwhelmingly clear.

Don’t suggest reviewers who work at the same institution or organization. Even if you don’t collaborate, the journal editor likely won’t choose them. Don’t choose present or former colleagues, coauthors, or collaborators, for the same reasons.

It’s perfectly OK, however, to invite people you’re acquainted with professionally. For example, networking at conferences can be a great way to meet other researchers whom you could eventually suggest as a reviewer. You can also ask your colleagues to recommend others they know in the field who could be qualified to critique your work.

Look for assistant professors and other earlier-career researchers rather than “big names”

“Big names” are high-profile professors in a particular field, such as emeritus professors or department heads. They usually appear as the last author on a paper, representing their position as the senior researcher. They’re typically very busy and don’t have time (anymore) for peer review. This means that they’ll probably decline the invitation to review your paper or never respond. It’s not to say it’s not worth trying, but you’re better off using your suggestions on reviewers who are both eager and likely to review your work.

Here’s a good workaround if an elite researcher is probably out of reach as a reviewer.

Each professor typically has their own research group, including several post-doctoral or Ph.D. students. These individuals have fewer departmental or teaching obligations and, therefore, more time to take on peer review. And, since they’re also aspiring to higher positions and greater research, they’re more likely accept an invitation to contribute to science by reviewing an article.

Start from the top (the “big name”) and work your way down the group’s hierarchy. First, go to the group’s website and check the group members for assistant and associate professors, post-docs, Ph.D. students, or even lab alumni. Typically, university websites will list their contact information on the group page.

Ph.D. students can also be excellent reviewers. You don’t necessarily need to have a Ph.D. to be a peer reviewer, but you do need to have expertise. Ph.D. students are an option because if they’re approaching the end of their degree and have already published papers or preprints in the area, they’ll be eager to take on a review and develop their career. Early-career researchers are, in fact, encouraged to do peer review to improve their skills and contribute to science.

Explain your suggestions

If you suggest reviewers in the cover letter or in the journal submission platform, explain your choices. The explanations shouldn’t be long: a sentence or two is fine.

Describe why the reviewer’s research is relevant to yours and why they might offer a valuable critique Use some of the keywords of your paper to demonstrate that the proposed reviewers are qualified to work on your paper.

Here’s a full example of what you can put in your cover letter when suggesting a reviewer.

Tomoko Suzuki, PhD University of Fair Review, Economics Department, Room 1 7-7-7 Chuo-ku, Tokyo, 100-1234, Japan Tel/Fax: +81 (0)55 555 5555 tomoko@fairreview.ac.jp • Dr. Suzuki has published extensively on monetary fluctuations vis-à-vis consumer behaviors. Notably, her work with Professor Juan Lopez and colleagues addresses similar themes to our present study.

Provide as much contact information as possible. You can also indicate researchers whom you do not wish to have as reviewers. Be sure to give a convincing reason, such as potential bias of a conflict of interest.

The best solution? Have our experts find reviewers for you

Maybe time constraints or a lack of connections keep you from suggesting good reviewers. No problem, Edanz has expert research consultants on hand and ready to closely examine your manuscript and do the reviewer research for you. They’ll compile a customized, diverse list of recommended reviewers that you can add to your cover letter or elsewhere in your submission. Explore the Edanz Reviewer Recommendation service here.

elp you put an end to unfinished, unpublished papers.