As a researcher, you’re motivated to challenge yourself to find out answers and to test question.. But while you challenge yourself, you come to find you’re competing with others.

Academic research is a very competitive business by nature. And of course, you want to “win.”

Winning help you toward promotion chances, a stronger reputation and influence, and more grant funding. It can even get you a better job.

So then, how do you win? And who really is your competition?

Competition is part of academia and you can win through better writing.

- In academia, who’s competing, and why?

- What makes a better, more competitive, research paper?

- Write better research that beats the competition

- Competition: For better, not worse

In academia, who’s competing, and why?

You won’t hear competition discussed much in academia. Unlike politics or boxing, it’s more under the radar. But it really matters.

Competition in research is for recognition, funding, or plain old ego/pride.

Human competitors

Your human competition includes:

- Colleagues in your department

- Workers in your research group

- Students in the same graduate program

- Researchers working in the same field, whether nearby or across the ocean

Invisible competitors

You’re also up against benchmarks and expectations. Some of these are self-imposed, some come from your institution. Some may be all in your head.

- How many papers have I published this year?

- Which journals are my articles published in?

- How many times have I been cited?

- How often have I been the first author? Corresponding author? Last author?

- Am I the best in my field? Will I ever be? Do I have potential? Where am I ranked?

and on and on…

Competition = publication

Competition, most often, comes down to published work. What you’ve published and where. And what happens after that.

Researchers assess each other based on the articles others publish and based on publication track record.

So, when an interview or assessment panel evaluates you, they’ll be thinking about your journals and their impact factors, your H-index, and your citations

Assessment metrics create an environment in which researchers are usually always aware of their own “score” and where it stands relative to the above-mentioned competition.

“There’s well-known competition among researchers for severely limited grant funding, publishing opportunities in prestigious journals, and for tenured positions.

There’s also lesser-known competition for institutional resources (who gets their preferred office space; who gets more administrative positions in their team), student allocations, and support for post-graduate and post-doctoral researchers

— Jacqueline Tudball, PhD

Edanz Author Guidance Consultant

What makes a better, more competitive, research paper?

A better research paper depends on who you ask, but certain traits are common. Journal editors are looking for these and so should you.

Novelty

Write an article that’s more interesting.

This may be a catchier or more novel topic for editors and peer reviewers.

It may be something related to a wider, cross-disciplinary question that many general scientists care about (such as climate change, urban growth, health, education).

It completely eliminates the “so what?” question in a journal editor’s head.

Now that’s a novel story!

Remoras pick where they stick on blue whales

In this study, the researchers found a type of fish that selectively places a suction mechanism near whales and, in a sense, “surfs” by them. The study rapidly inspired work on suction devices for attaching cameras to endangered marine species. A novel story inspired more research.

That’s a winner.

Intrigue

This means something that readers will pull readers in. They’ll want to read your article to find out the answer to the question or situation you addressed.

Step back from your precise focus and think about the bigger picture. How do you explain your research topic – your message – to someone you’ve just met. What’s really interesting about your results? What’s your elevator pitch?

If you can’t, you might be lacking intrigue (or just not that interested in your topic).

Readers are your key stakeholders. They’re the ones who may cite your article. Attract them and reel them in.

Now that’s an intriguing story!

The title’s a mouthful (read on for how to fix that), but that’s not the point here. It’s descriptive and will attract readers who can understand the topic. The researchers studied an ancient supervolcano in Indonesia. They were able to theorize that such volcanoes actually erupt thousands of years apart.

Supervolcano eruptions can dramatically change the Earth’s climate, so this story isn’t only a fascinating drama, it has crossover appeal with sciences such as ecology and climatology. And it hooks the general public, which is why is made such a great story for the press. Even better.

Another winner right there (until the volcano erupts).

A better publishing journal

Write a manuscript that will get published in a journal with a higher impact factor or otherwise highly regarded. Also, try to choose on that has open access so it’s more accessible.

Your aims are to get noticed, be cited, and to inspire. Think about reach, readership, and accessibility. These factors get you in a better journal and increase the chances of being cited.

That’s the bigger picture. Now let’s look at specifics.

Write better research that beats the competition

Write better and win. Especially if English isn’t your first language, that can seem hard. But a simple truth is that many researchers are working too hard and too fast to focus on their quality.

This is where you can get ahead by putting in a little extra attention.

Follow these tips for better, winning research writing.

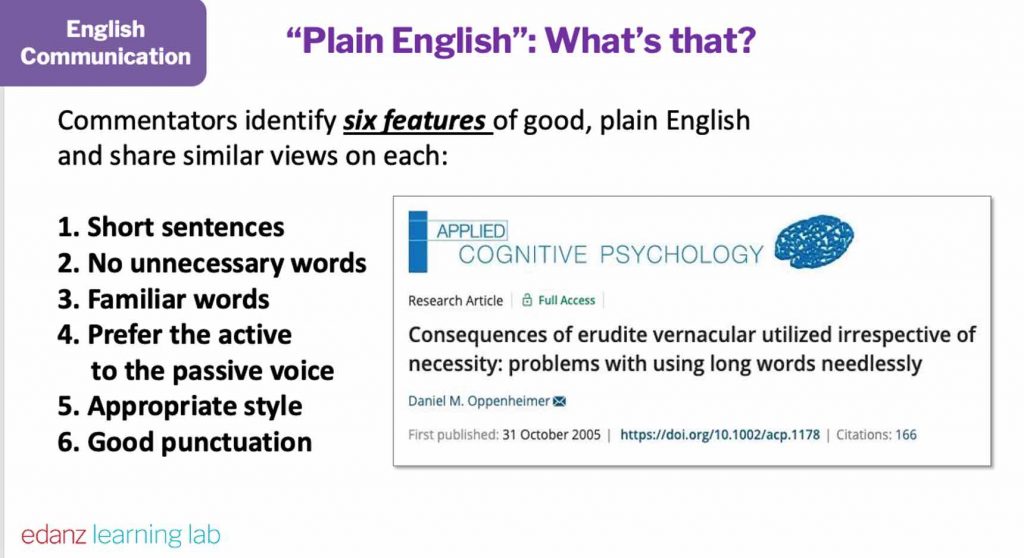

Simplicity and clarity

Keep your message clear and simple when writing.

Don’t get side-tracked. Good, effective, research articles address specific questions that are interesting for readers.

Before beginning a project, think about what question you’re testing. Make sure you address that specific question with the data you collect. Limit yourself to that question in your manuscript. Too many research papers go off on tangents and end up confusing readers.

Plain English is your friend and your reader’s friend.

“Plain” and “simple” does not mean “dumbing down” your language; rather, it means using more easily and widely understood words when you can.

The Plain English Campaign recommends:

- Short sentences (around 15–20 words tops)

- Active verbs (GOOD: “We found…”, NOT SO GOOD “It was found that…”)

- Use “you” and “we” (this also encourages use of an active, not passive voice)

- Use words suitable for the reader (this applies for all writing, but don’t confuse this with overloading your writing unnecessarily complex terminology)

- Don’t be afraid to give instructions

- Avoid nominalizations (these are names of processes, etc. in place of verbs; e.g., GOOD: “We discovered a new type of plankton.”; NOT SO GOOD: “Our findings yielded the discovery of a new type of plankton.”)

- Use lists where appropriate (like this one)

Hook readers with your title

Your title captures your reader’s attention the same way a catchy title in your Facebook feed makes you click. Together with the abstract, the title “sells” your work.

Use it to hook the reader. Capture their attention to differentiate your work.

A good title will:

- Give a specific but concise indication of what work was done

- Guarantee that someone interested in the topic will read on to the abstract

- Be “descriptive, direct, accurate, appropriate, interesting, concise, precise, unique, and … not be misleading” (Tullu, 2019)

Research varies on the title length, with some indicating more citations for shorter titles, and other finding the opposite. Don’t get hung up on length if it’s necessary for accuracy and for attracting interested readers (like with the above volcano story), but do aim to eliminate excess words.

How to structure the title

You can give details (descriptive), stating the main finding (declarative), or give a query or your research question (interrogative), though the latter is better suited only to reviews and less suitable for research (Tullu, 2019). Interrogative titles can seem sensationalist and are usually better saved for your press release.

Each of these titles is effective in its own way. Each delivers the specifics and has an element of intrigue to make the reader continue on to the abstract and the article itself.

- Discrimination as a self-fulfilling prophecy: Evidence from French grocery stores

- White and wonderful? Microplastics prevail in snow from the Alps to the Arctic

- Yoga decreases insomnia in postmenopausal women: a randomized clinical trial

More title tips:

- Avoid acronyms unless they’re widely known outside your area of specialty

- Add in keywords so they’re easier to search for

- Consider if it’s really necessary to include the study design (sometimes a journal will require it)

- Think what words your ideal reader will be attracted to

- Read more titles and reflect on what makes you read on

Unlock discovery with keywords

Carefully choose your keywords to increase chances your article will be discovered.

Use resources like MeSH on Demand to find useful keywords (some journals require MeSH headings).

Add them to the title and use the maximum keywords you’re allowed by the journal. Repeat these keywords throughout your paper, especially in section headings and at the end of the Introduction.

Make your keywords precise, seeking to eliminate conjunctions, articles, and other non-essential words.

A search method for keywords

Identify 12 keywords using lists, MeSH or other articles and then discard 3-4 of them.

- Then use 2 in the title

- Use as many as you can in the keyword list

- Then 3 keywords 3–4 times in the abstract

- And make sure they’re used throughout the paper at suitable times

Clearly set out your aim at the start of the introduction

Introduce your question here. Tell your readers how you will address this issue, or test your hypothesis, at the end of the Introduction (“Here we show …”).

Follow the Nature and Science method

To see this at work, read the end of the Introduction in all Nature and Science articles.

These articles always have a basic three-part Introduction:

- The question the article will address;

- Recently published (review) articles that set the scene, give the “state-of-the-art”, and;

- A final short section that clearly tells the reader what the article will do. “Here we show …”

Also, tell your readers the answer to the question at start of the Discussion. That provides a transition that moves the reader along comfortably.

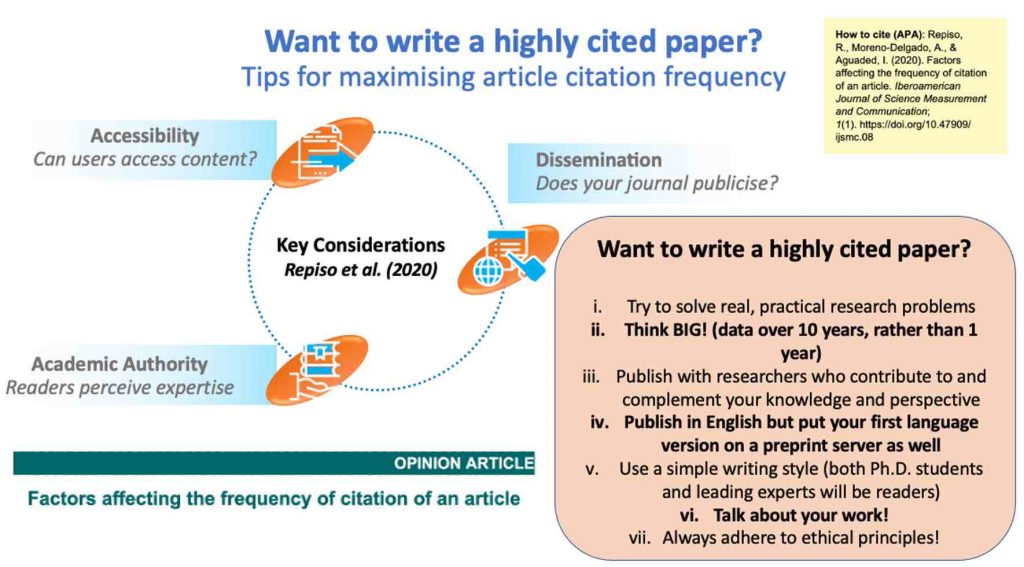

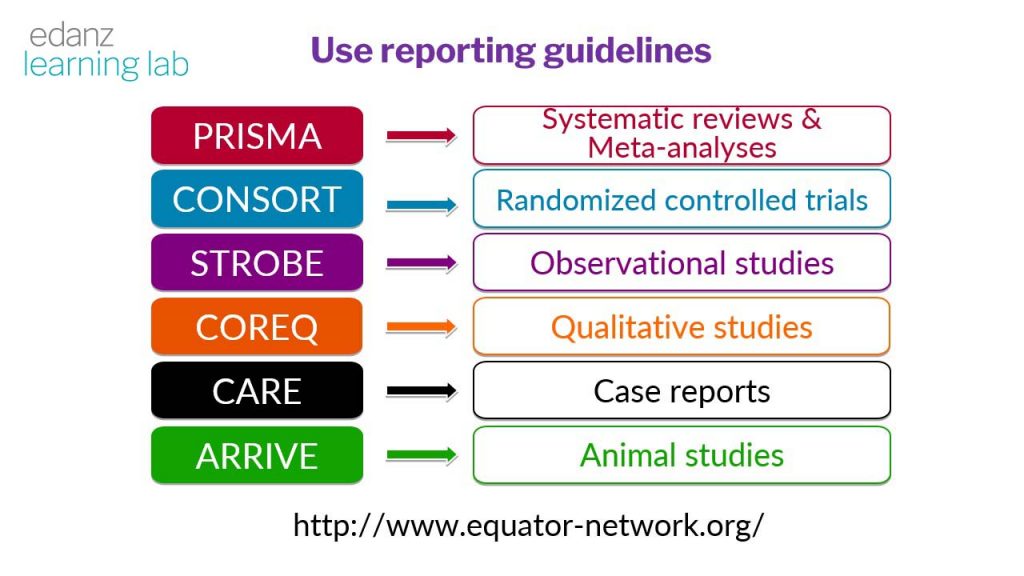

Know your reporting guidelines

Journals want to see certain kinds of structures present in certain kinds of research, for ethical and production reasons.

Give them what they want and make them happy. This is good writing and good publication ethics.

Check EQUATOR and familiarize yourself with the appropriate reporting guidelines specific to the kind of paper you plan to write (STROBE for observational studies, CARE for case reports, etc.).

Consult with a statistician

If you’re doing quantitative work, or testing a question that requires numeric analysis, talk to a statistician early on in your research.

Find a colleague in your department or university (perhaps in your research group) who is numerically inclined and ask them many questions. Buy them a coffee, or tea, for their trouble. See if you can help them by connecting them with someone or offering advice in your own area.

Make sure your data tests your question and that you have a plan for a meaningful (not needlessly complex) analysis.

So many manuscripts get lost in unnecessary detail or present data that aren’t even necessary to address a particular question.

By sitting down and discussing your work early on with an analytical expert you’ll be able to focus both your question and the data needed for any subsequent analyses.

You’ll also be collecting data with your analysis type in mind, appropriate for the question you plan to answer.

Journals use specialist statistical reviewers, so don’t get caught out at that late stage.

Edit for readability before submission

First drafts are just that: drafts. They don’t have to be winners, but they do have to be the start of a winner.

Read your work aloud to ensure that sentences make sense and are crisp, clear, and concise. Less is more: 15–20 words per sentence is sufficient with one idea in each. Limit your use of complex words. Use fewer acronyms and abbreviations, especially those which will not be familiar to those outside your field.

Readability means simple (as easy to read as possible) when writing better manuscripts.

The better works have been thoroughly checked and read by all contributors before submission. This is also a basic ethical requirement: All authors listed on a paper must have had the chance to contribute to the text and make changes (ICMJE guidelines).

Following ethical authorship requirements also helps to improve the language, but again: keep things simple. You’ll need to designate one author to manage this process, to act as the arbiter and complete the final edit. This is usually the corresponding author on academic articles.

Competition: For better, not worse

“Competition exists as it does in any other field where you are vying for limited fixed-term positions with too many qualified people. But, in academia it just feels more cutthroat. Ultimately, direct competition with people in your lab is detrimental in the long term.”

— Vishal Gor, PhD

Edanz Author Guidance Consultant

Writing a “better” paper, getting ahead of the competition, being a successful academic requires a set of skills that are quite distinct. The skills needed to perform good research are distinct from those needed to effectively compete.

So while you’re keeping your publication rate up, you’ll also be turning out competition-beating work.

Some final thoughts:

- Keep track of others, but don’t obsess and don’t overlook chances to help others as well

- Be aware of your own scores and how you compare, then find practical ways to raise them

- Select journals with quicker turnaround, good reach, and a strong reputation in your field

- Be aware of the times journals take for papers to get published

You’re doing good research and have an inquiring mind to search important questions, but are you able to write manuscripts that achieve success?

Good luck with your next research manuscript. Make it a winner! And if you want to train yourself up to even higher levels of writing ability, take a course at the Edanz Learning Lab.