“Don’t Look Up” is Netflix’s most-watched movie ever, and it’s about… science.

Even if the movie is a bit extreme and silly, it has valuable lessons for researchers.

“Don’t Look Up,” in its own Hollywood way, addresses:

- The need for researchers to publish

- Peer review

- The relationship of academia, industry, and government

- Why it matters little where you study and work

- The importance of scientific communication

It’s great to see the importance of research in the mainstream. And while the movie obviously is a bigger statement about the climate crisis and Western society, it’s also a big endorsement for good research and good scientific communication.

Here’s how to watch (or rewatch) this movie.

A very popular movie… about science

“Don’t Look Up” is a comedy-drama about scientific discovery, in a Hollywood way.

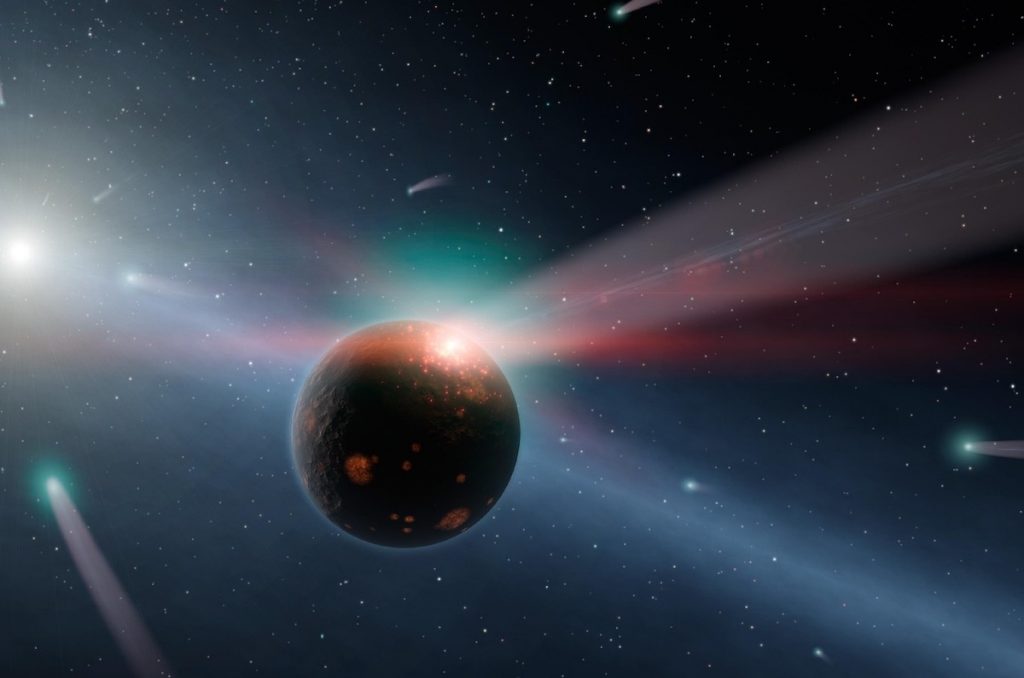

PhD candidate Kate Dibiasky (Jennifer Lawrence) discovers a comet on a straight collision route with the Earth.

She finds it by chance and her adviser Professor Randall Mindy (played by Leonardo DiCaprio) confirms it with all sorts of high-level math.

These scientists then urgently try to convince the public to pay attention before the comet smashes into the Earth.

It doesn’t go well.

From the TV news shows to the U.S. Department of Defense, no one takes Mindy and Dibiasky seriously. Except for other scientists.

Eventually, the comet gets on the U.S. President Orlean’s (Meryl Streep) radar. Money and industry greed gets involved. Mindy gets seduced by fame. We won’t spoil the rest.

Here’s the trailer if you haven’t seen “Don’t Look Up” yet.

Communicating science, we learn, sure is hard! It’s unlikely you’ll discover a deadly comet in the next day or two, but you will find things. How you manage your research career, understand relations, and communicate your work may be the difference between relevance and mere survival.

The importance of publication

DiCaprio’s character, Dr. Mindy, is as a smart astronomer and professor at a good school, and he’s only in his 40s. He is, as the movie site IMDb says, a “low-level astronomer.”

But when he’s trying to get attention about the comet, he blurts out, “I haven’t published in a while, so you probably haven’t heard of me.”

This detail may be lost on common viewers. It’s like he’s talking to himself because no one cares what he says. But fellow researchers know why this matters.

Publication is competition

Competition inside academia is tough and you need to keep ahead. Publication is a researcher’s mark of achievement, and how they achieve impact. It’s also how you get more funding for more research, reflects well on yourself and your institution, and above all, disseminates your findings.

Being published in a journal with a higher impact factor (IF) boosts your reputation and may increase how often you’re cited. Researchers like to cite highly reputed researchers. More publications can increase citations and attest to your productivity.

It’s often even a requirement.

Be careful where you publish though. Avoid pay-to-play publication scams (i.e., predatory publications), consider options such as preprints and open access to expand your readership. And choose your target journal carefully.

Sometimes it’s not all about impact factors, especially if you’re in a highly specific or regional area of research.

So, why didn’t Dr. Mindy get published?

Dr. Mindy, despite his intelligence, looks ashamed about his publication record.

Why hasn’t he “published for a while”? Maybe:

- He’s in a lower-pressure environment

- He hasn’t had any good research ideas

- He’s not active in his field or the greater scientific community

- He lacks funding, connections, inspiration

- He has personal issues

They’re all realities for researchers. Through networking, connecting with those both immediately around you, and keeping open to new ideas, and getting peer feedback, you can break through many of them.

In the movie, sadly, Dr. Mindy loses sight of his need to publish and his role as a researcher. Fame wins him over, even with a deadly comet approaching. He definitely has personal issues.

Understanding of peer review

Both Mindy and Dibiasky hold the peer-review process in high regard. Peer review is mentioned around a dozen time in the movie when alluding to a study that has credibility. It may be the most mention that’s ever been made of peer review in a major movie.

The movie gets the importance of peer review right, at least at a basic level.

Peer review remains the gold standard for weeding out poor research and validating good research. Though it’s not perfect. The process is evolving, too, as it needs to.

The main points of peer review are that it:

- Acts as a filter to ensure that high-quality research is published. Peer reviewers determine the validity, significance, and originality of the study.

- Aims to improve the quality of articles that are suitable for publication by identifying problems in methodology, logic, and language.

There are some things, however, that peer review doesn’t do, as we discussed in this post.

The vapid TV hosts, and the U.S. President, shrug it off in the movie. They suggest the research isn’t valid unless it’s reviewed by Ivy Leaguers or NASA.

Really, they only care about the storyline and about power. The movie’s a good start. It’s clear that the researchers didn’t write the script. So perhaps science could do a better job of communicating the value of peer review.

Peer review is changing

“Don’t Look Up” responsibly mentions peer review, if only at a superficial level. It matters, but things are evolving in this area.

The movie also gives an extreme example of how peer review may slow things down. It can take months, or even years. So if you do find a comet on a rapid crash course with Earth, you may not have time for this process.

Preprints are one attractive solution that’s emerging for speed up research dissemination. A preprint can have your research up in days. Instead of peer review, it’s then subject to community review, which lets you improve your work, and eventually submit it for proper review.

This benefits of this mode of communication were clearly on display with COVID-19 research. In this urgent environment, researchers were rapidly able to share new data and findings. Many were not yet validated, but preprints let them be made public, researchers could attach an identifier to them so their work wasn’t “stolen,” and society as a whole often benefited.

Relationship of academia, industry, and government

In “Don’t Look Up,” the academics discover the comet and want to alter its course to save the planet. The U.S. President wants to get rid of it somehow, and get credit for it.

Enter industry. Peter Isherwell (Mark Rylance) is a creepy and soulless mashup of Steve Jobs, Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, and Jeff Bezos. The tech mogul, despite being an awkward presence with vague ideas, has President Orlean’s ear whenever he wants it, because he’s a billionaire and a donor.

He has a plan to use robots to mine the comet for precious and valuable metals. With deep pockets and the President’s support, his big tech company takes over.

How the roles are defined

With industry replacing academia and leading the response to the comet, the roles became:

- Academia: Protect the science, make the right choice, but lured by money

- Industry: Profit at all costs, facilitating science but with its own interests first

- Government: Power, donations, control

In “Don’t Look Up,” academia makes the discovery, government ignores it until industry hijacks it for profit. Academia, and valid science, then take a backseat.

Watch the movie to see how Isherwell’s BASH plan turns out.

“Don’t Look Up” isn’t far from reality: a Harvard study evaluated that across all industries, politically connected firms account for a third of total employment. The study also found that the more regulated the industry, the more pervasive the political connections were in that industry. Industries such as pharmaceuticals, banking, and telecom are prone to high levels of regulations. Thus, private firms in those industries often have more political connections.

The reality

In fact, there are many superb collaborations involving academia and industry. mRNA vaccines, for example, have been an ongoing interplay of academic research and industry application. How they’ve been used, inequitable distribution, and government hands are all topics for debate, however.

At a more local and effective scale, we can find an example from Edanz’s home base in Japan. Here, the triangle is pragmatic and not so far-fetched. Academia, funded by government, makes discoveries. Industry implements them. Government facilitates the implementation.

Image credit: Meijo University

The triad is a literal disaster in the movie. In real life, though, it’s not all bad news.

Where you went to school, where you work

Ivy League, noted by the President’s son and Chief of Staff, is code for “the best schools.” Politics, sadly, often endorses this view. About half of U.S. presidents in the past century were from Ivy League schools, including Obama, both Bushes, and Clinton. Of the U.K.’s 55 prime ministers to date, 48 went to Oxford, Cambridge, Edinburgh, or Glasgow.

Ivy League, Russell Group, or you’re worthless?

Indeed, prestigious U.S. Ivy League schools like Harvard and Yale rank highly in many areas and are notoriously hard to get into. In the U.K., the Russell Group is the equivalent.

In Japan, it’s The University of Tokyo and Kyoto University. Korea has Seoul National University. There are Tsinghua and Peking in China. And so on.

Are elite schools the best schools?

Is a researcher or student from a public institution or one in a developing economy less capable or important?

We should certainly hope not! It would deprive us of many great minds and discoveries. Getting into Oxford, Stanford, or MIT is a momentous achievement. Yet it can also owe to wealth and privilege, test scores, and luck. Where does that leave the bad testers, low-income learners, and those born into disadvantage?

Public universities rank among the world’s best

Among Smithsonian Magazine’s top recent science discoveries are those from schools such as the University of Nebraska (U.S.), Technical University of Munich (Germany), and Lund University (Sweden). These are all public schools.

In “Don’t Look Up,” the researchers are from Michigan State University (MSU). MSU, according to the QS rankings has the #97 astronomy program in the world. Far below #3 Harvard and #9 Princeton, both elite Ivy League schools, though nothing to sneeze at.

To the thick-headed Chief of Staff in the movie, it’s not Ivy League so it’s laughable.

The film’s writer-director Adam McKay said he wanted to make a point that “total dolts” can go to Ivy League schools like Yale and Penn, while less-prominent schools can still give top-level educations.

Elitism hurts science and marginalizes regions and researchers

Another point to consider: university elitism may damage science and continue to disadvantage developing countries. This happens as a monopoly effect. Only certain universities are credible. Students want to study and work there. Those universities can then choose the best of the best.

This can lead to brain drain from under-developed and developing economies. As the best minds go abroad, or hole themselves up in certain institutions, they are a loss to their communities. That’s true in advanced economies as well.

“Don’t Look Up” gets that, at least from an American perspective. Yes, they exaggerated. Anyone reading this knows Harvard and Oxford. But do you know UNICAMP in Brazil? Universidad Central de Venezuela? University of Ibadan in Nigeria? All are fine schools. All advance good research. As does Michigan State. Go Spartans.

Scientific communication is vital

That’s a diverse bunch of topics. But in a sense, they all fall under the single umbrella of communication. Communication, in the movie, is a wreck. Only the scientists and their families (eventually) seem to know how to work together.

Almost no one understands anyone else

Part of the problem is the lack of mutual understanding. The academics talk like scientists, which makes them very hard for the public to understand. Government and industry for the most part, are all horrible people, yet they can’t even communicate with one another. All their communication seems transactional and based on gratification.

As a scientist, you can make it your job to communicate the significance of your ideas in language that people can understand and relate to. You’re working with complex concepts. Yet, no matter how complex, you’re doing it for a reason, right?

What is that reason?

How will you explain it to a lay audience?

In much the same way you have to make your research posters accessible to more than other researchers…

You have to make your science more accessible

So, how can you do this? For starters…

- Use lay abstracts, graphical abstracts, and plain-language summaries

- Limit your jargon

- Deeply consider real-life implications outside your research “bubble”

- Write a press release aimed at non-scientific media

- Talk with everyday people to see what they’re thinking

- Visit a school class and explain your work

“Don’t Look Up” is a dark and disastrous comedy. It’s a cartoon of real life, but it tells us a lot about how the public perceives science. It seems we’ve got a lot of work to do.